PROgress Implementation Toolkit

This website was made possible by funding from ViiV Healthcare, a global specialist HIV company established in 2009, majority owned by GSK, with Pfizer and Shionogi as shareholders

Authors

Rob J. Fredericksen, PhD, MPH – University of Washington, Medicine, Seattle, USA

Duncan Short, PhD – ViiV Healthcare, Global Implementation Science, UK

Emma Fitzsimmons, BA – University of Washington, Medicine, Seattle, USA

Justin McReynolds, MS – University of Washington, Health Informatics, Seattle, USA

Sierramatice Karras, BS – University of Washington, Health Informatics, Seattle, USA

William Lober, MD – University of Washington, Health Informatics, Seattle, USA

Heidi M. Crane, MD, MPH – University of Washington, Medicine, Seattle, USA

Foreword

This PRO Implementation Toolkit was assembled by the PROgress Study Team from the University of Washington and ViiV Healthcare, and reviewed by the PROgress Study Steering Group. The purpose of this document is to provide practical insights gathered from the implementation of patient-reported measures and outcomes (PROs) into routine HIV care to support those who may be considering this process.

PROgress is a research workstream entitled ‘Improving HIV care through the implementation of PROs within routine patient management’. This is comprised of three complementary components:

- An implementation science research study (the PROgress study), integrating PROs into two HIV clinical care settings. This served two purposes: first, to identify the essential program elements that can support the sustainable implementation of PROs into routine HIV care in community settings; second, to examine the added value of implementing PROs into routine HIV care for the salient stakeholders, including the patient, the providers, and other clinic staff.

- An Evidence Review and Summary, which is designed to raise awareness of the evidence relating to PROs in the care of people living with HIV (PLHIV) and to outline the potential for well implemented instruments within routine care. It draws on evidence from published literature characterizing the impact of PROs in routine clinical care for patients with chronic comorbidities including HIV-related literature as well as other fields, particularly oncology

- This PROgress Implementation Toolkit, which is a resource for those considering implementing PROs in clinical HIV care. This is designed to provide practical advice to support the introduction of clinical PRO assessments into routine HIV care. These insights draw from a range of sources, including: practical experience integrating PROs into HIV clinical care at multiple sites, including the PROgress sites; published literature; and additional primary interviews with stakeholders that have experience integrating PROs into HIV clinical care. This Toolkit was designed to provide resources, tips, and learning to help implement PROs adapted as needed for individual clinics.

The PROgress Implementation Toolkit and Evidence Review and Summary, serve as complimentary resources, with the Toolkit designed to provide practical hands-on approaches and the Evidence Summary designed to summarize available real-world evidence supporting the integration of PROs within routine HIV clinical care settings with each informing the other.

Introduction

What is a PRO?

A patient-reported measure or outcome (PRO, also less commonly known as PROM) is defined as “any report on the status of a patient’s health condition that comes directly from the patient without interpretation of the patient’s response by a clinician or anyone else”.1

PROs provide the patient perspective of the effects of disease and treatment including comprehensive assessment of factors such as mental health symptoms like depression/anxiety, well-being and satisfaction, health behaviors such as medication adherence, risk behaviors such as substance use and sexual risk behavior, as well as other social determinants of health and practical or safety information such as housing status and intimate partner violence.

How PROs integrate into clinic flow

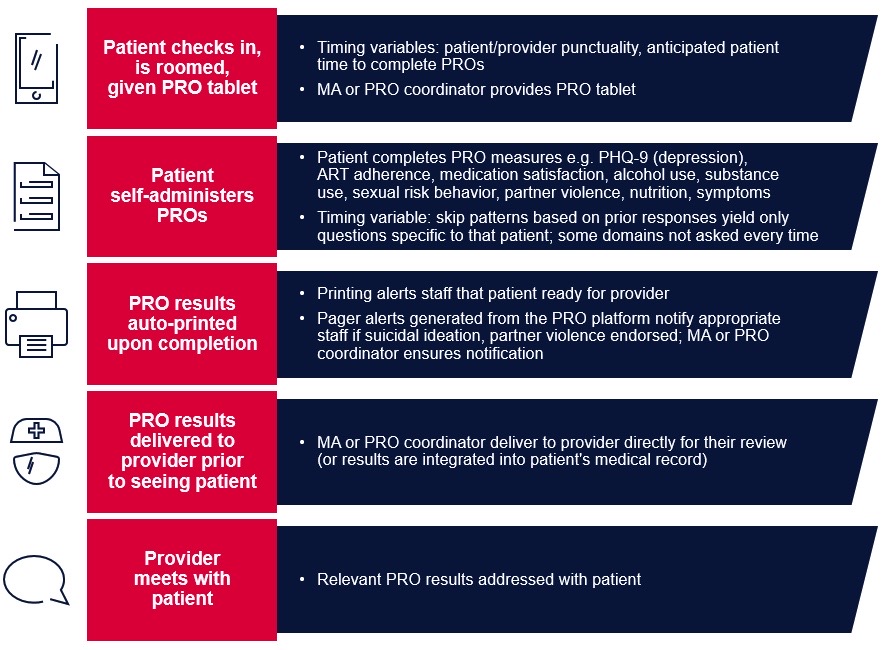

What might the end result of PRO integration into care look like? How will it fit into existing clinic flow? Figure 1 below, based on clinical integration of PROs in the PROgress study in two HIV care clinics, provides an overview of what happens and when.

Figure 1. PRO implementation example in HIV clinical care

Evolution of PROs in care

While historically PROs have had a much larger role in research than care, the use of PROs in clinical care has been increasing as a result of several key developments. These include the rapid progression of technological infrastructure leading to the expanded incorporation of touch-screen tablets, internet-based applications, and electronic health records (EHRs) in clinical care.2 Furthermore, PROs are increasingly demanded by regulators, payers, accreditors, professional organizations, and providers to measure and address PROs at the level of the patient, clinic, and healthcare system as well as provide population information.2 Legislative demands to improve healthcare outcomes without increasing costs has put more emphasis on quality of care, value-based reimbursement, and patient engagement. As such, PROs have been increasingly identified as the most direct and relevant measure to demonstrate high-quality patient-centered care.2 The most common reasons cited for implementing PROs in clinical care among stakeholders who have already implemented them included screening, monitoring, treatment evaluation and treatment planning, and quality improvement including that mandated by external agencies.3 Other reasons cited in interviews of respondents from a range of healthcare settings in which PROs had been implemented included shared-decision making between patients and providers, and, less often, reasons related to satisfaction or reimbursement.3

Relevance of PROs to modern HIV care

Advances in antiretroviral therapy (ART) over the past decades have increased the life expectancy of PLHIV and transformed HIV from a fatal disease to a chronic manageable condition.4 The associated decline in mortality since ART has been introduced has led to increased emphasis on managing quality of life (QoL) and comorbidities, including those associated with HIV and its treatment. Many of the symptoms, health behaviors, and life circumstances associated with living with HIV and these comorbidities are not directly observable and are more easily measured by direct patient report. Yet, many such variables are under-addressed and not measured well in clinical care: in HIV care, examples include antiretroviral (ARV) medication adherence, substance use, sexual risk behavior, and depression.5 Reasons for this have included social desirability bias, time constraints, limited communication skills to convey symptoms or feelings, or linguistic and/or cultural barriers.6-9 PROs help address these barriers. On-site PRO collection prior to routine clinical care appointments, via hand-held computer tablets with real-time results available to providers during clinic visits, has improved provider ability to detect and address depression/suicidal ideation, inadequate ART adherence, and substance use in HIV care.5,10 Integrating PROs into clinical care of patients with chronic conditions, such as cancer, rheumatoid arthritis, and HIV, have been shown to be acceptable to patients and providers and valuable in clinical care;10-12 they have improved patient-provider communication13-17 and increased patient satisfaction with care.16,18-20

Evidence-based support for PROs in HIV Care

PROs have been highly useful to providers and acceptable to patients. An in-depth review of evidence (PROgress Evidence Review and Summary) details this here and supports the idea that implementing PROs in HIV care can:

- Improve detection of health behaviors, symptoms, and mental health issues

- Increase both provider awareness and interventions to address depression, drug and alcohol use, intimate partner violence, and other domains in order to improve health outcomes

- Improve patient-provider communication, by helping patients prioritize and raise concerns, and by helping providers identify and initiate discussion of less-observable issues and/or discussion of topics that are highly sensitive or personal to the patient (e.g. depression, substance use, sexual risk behavior)

- Improve delivery of care, for example, allow providers to focus on the most relevant issues during the visit, increase referrals, more closely monitor treatment, and improve symptom management

- Improve outcomes such as depression scores and symptom burden.

Toolkit purpose

This Toolkit provides practical advice to support the introduction of clinical PRO assessments into routine HIV care. These insights draw from a range of sources, including practical experience integrating PROs into HIV clinical care at multiple sites, published literature, and interviews with stakeholders with experience integrating PROs into HIV clinical care. While some of the information in this Toolkit applies to all formats of PRO assessment, we focus on implementation of tablet-based patient self-administered PRO assessments in clinical care due to the clear advantages outlined in Chapter 3. Given differences between HIV clinics, a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach to PRO integration is unlikely to fit every clinic’s needs. With this in mind, this Toolkit provides resources, tips, and effective practices to help implement PROs adapted as needed for individual clinics.

Chapter overview: steps toward implementation

Though the process of PRO implementation is iterative, the chapters of this Toolkit sequence tasks into a general chronologic order starting with planning and decision-making (Chapters 1–3), then implementation (Chapters 4–6), and finally ongoing collection, maintenance, evaluation, and improvement (Chapter 7).

Chapter 1 helps assess and improve a clinic’s readiness for PRO implementation.

Chapter 2 offers a pathway for stakeholder engagement.

Chapter 3 itemizes steps needed in order to build technical infrastructure for electronic data collection.

Chapter 4 operationalizes important steps to create a PRO assessment that best suits the needs of an individual HIV clinic and its patients.

Chapter 5 outlines the decisions and protocols to support integration and ongoing success.

Chapter 6 offers insight into initial and ongoing staff training needs.

Chapter 7 provides strategies for monitoring, evaluating and sustaining the success of integration of PROs into clinical HIV care.

How this Toolkit was developed

Evidence and practical tips found in this Toolkit are drawn from real-world PRO implementation experiences and data collected from:

- The PROgress study, a ViiV-funded project evaluating impact, effectiveness, and sustainability of PRO collection in routine clinical HIV care at Midway Specialty Care in Ft. Pierce, FL, and St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, ON. The study and Toolkit were developed in conjunction with a Steering Committee comprised of HIV care providers, PLHIV, and HIV care researchers

- The Centers for AIDS Research (CFAR) Network of Integrated Clinical Systems (CNICS), a network of eight United States (US) HIV clinics. As of early 2020, >85,000 clinical PRO assessments had been completed by >20,000 PLHIV across CNICS sites as part of routine clinical care visits to improve care and facilitate research on health domains important to long-term outcomes among PLHIV.

Language

There are a number of acronyms throughout this Toolkit. They are defined in Appendix 1. We also define terms that may be unfamiliar or whose meaning differs by context with use. For example, we use the term provider to refer to the physician, fellow, nurse practitioner, physician assistant, or other clinician who is providing patient care. We realize in different contexts, terms such as provider have broader or narrower meaning.

Resources

1. ASSESSING AND IMPROVING READINESS TO IMPLEMENT PROs IN HIV CLINICAL CARE

1.1 Are PROs right for my clinic right now? If not, how do we get there?

The appropriateness and readiness of PRO integration in your clinic depends on many factors including the patient population, needs and perceptions of clinic leadership and providers, logistics, technical capacity, and cost. The tool below is designed to help you assess and improve the feasibility of integrating PROs in your clinic within each of these dimensions, by helping envision how to overcome barriers.

Patient population:

Does the majority of the clinic patient population possess literacy skills to read at 6th grade level (approximately ages 10–11)? Yes/No

If ‘No’ (or unsure): PROs that are based on text only may be appropriate for only a subset of the population. An enhancement to text is use of a pre-recorded voice to help guide patients through a brief set of PROs. While this has advantages if reading levels are low, it adds a great deal of time/patient burden to the assessment and therefore should be considered only if needed or only for those patients who need it.

Does the majority of the clinic patient population possess the cognitive and physical capacity to complete a brief PRO assessment? Yes/No

If ‘No’: self-administered PROs may be less appropriate for these patients, and time may be better spent eliciting verbal self-report or the report of caretakers. Clinic staff may need a consistent means of distinguishing these patients from those with the ability to self-administer PROs. Of note, the ability to complete a brief PRO assessment on a tablet has been found to be feasible in many patient populations including the elderly (particularly if no mouse or keyboard as in tablets),21,22 and broadly among diverse populations of PLHIV.23,24 This is often much more feasible than expected.

Clinic leadership:

Is the clinic’s leadership likely to support the implementation of PROs? Yes/No

If ‘No’: consider what is driving this perceived lack of support. What are the clinic leadership’s key goals and priorities, and what evidence regarding the use of PROs may align with them? Leadership typically supports PRO implementation for a variety of reasons including improving patient care, better assessing needs, and enabling better data collection for administrative tasks such as mandated reporting and quality assurance from external agencies (See Chapter 2 – Engage Stakeholders).

Is there an individual or individuals on staff that can cultivate stakeholder interest in PRO collection and champion PROs as a priority? Stakeholder support or clinic champions have been critical for successful integration of PROs in clinical care.6 Yes/No

If ‘No’: see Chapter 2 – Engage Stakeholders which offers support for illustrating the benefits of PROs in clinical care.

Is there an individual or individuals on staff that can champion PRO data collection with respect to managing day-to-day operations? Yes/No

If ‘No’: consider what steps would be needed to identify such an individual or allot time in an existing individual’s duties that would be accountable for the ongoing success of this operation. For example, this individual may supervise front desk staff, or may be a designated medical assistant (MA).

Providers:

Are clinic providers supportive of the use of PRO measures in clinical care? Yes/No

If ‘No’: consider the basis for this. What are their perceptions of the value of PROs? What experiences form their basis for the lack of support? What are their concerns (see Chapter 2 – Address Common Concerns)? Have your providers had negative experiences with PROs? To what extent could these concerns be addressed? Provider concerns often focus on potential impact on clinic flow or visit length. Does focusing on specific, difficult-to-assess domains relevant to improving care, such as substance use or intimate partner violence, impact support? Does focusing on a brief assessment, with plans to implement in such a way to minimize impact on flow, minimize these concerns?

Has their response to changes in prior clinic protocols been positive? Yes/No

If ‘No’: identify the key factors driving this. Evidence supporting the benefits of PROs to improve clinical care may minimize these concerns (see Chapter 2).

Logistics and flow:

Can the clinic allot time at the beginning of the visit for patients to take a PRO assessment without disrupting flow? Yes/No. Note: amount of time needed will depend on assessment length.

If ‘No’: do opportunities exist to collect PROs from patients while they are waiting for their provider, or off-site, using personal electronic devices?

Note: while off-site PRO administration may lessen the impact on clinic flow, as a standalone approach it excludes patients who lack such devices. It may however be useful as a supplementary approach to within-clinic PRO collection to decrease impact on clinic flow. This may be a particularly useful approach in care settings with telehealth visits, an increasingly common practice as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. See Chapter 5 – Outline Workflow. A PRO timing estimation tool is available here.

Does the clinic have a plan to allot space on-site for patients to self-administer a PRO assessment? Yes/No

If ‘No’: can patients complete the PROs while they are waiting for their provider in the examination rooms, or off-site? See above note regarding off-site PRO administration.

Technical capacity:

Does the clinic have the technical capacity to support electronic data collection? Yes/No

If ‘No’ (or unsure): see Chapter 3 –Technical Choices and Infrastructure.

Cost:

Can the clinic afford the resources necessary, such as the staff time and equipment (e.g. iPads or other tablets)? Yes/No

If ‘No’ (or unsure): see the next section Start-up and recurring costs.

1.2. Startup and recurring costs

Understanding the financial costs associated with implementing PROs is fundamental to long-term success. There are different types of costs to consider: initial start-up (or one-time capital costs) and recurring fixed costs.

Start-up costs bring a project to operational status (e.g. software development, purchase of office equipment, licenses, etc). These costs are incurred at the beginning of the project or at a single point in time, and not as a year-to-year or month-to-month expense.

Table 1 contains typical start-up costs to consider when developing a program budget.

| Table 1. Typical start-up or capital costs | |

|---|---|

| Budget Category | Description |

| Clinic Personnel |

Dedicated staff to oversee the PRO implementation (often existing clinic staff who manage this as part of their portfolio of duties). Tasks include:

|

| Office expenses |

|

| Equipment |

|

| Communication |

|

Of note, some costs (e.g. internet) will not apply to many clinical settings, as these resources are already available. Personnel are likely the most important component of costs in many clinics, whether it is adding new staff or reallocating duties. IT costs can include platform development versus integration of existing platforms (several are available as shareware but will still require programming [see Chapter 3]).

Recurring costs occur on a regular basis, and typically fall within an annual budget period. Unlike one-time costs, recurring costs generally remain the same within the budget year (e.g. general administrative costs, rent, license renewal, etc). However, normal price increases (e.g. rent increases, pay raises, or other cost-of-living increases) should be budgeted for each coming year. Again, many of these will not apply to many clinic settings however, personnel considerations are key.

Table 2 shows examples of recurring costs.

| Table 2. Examples of recurring costs | |

|---|---|

| Budget Category | Description |

| Personnel |

|

| Office expenses |

|

| Equipment |

|

| Communication |

|

| PRO licenses |

|

Again, some costs, such as internet use, will not apply in most clinical care settings (e.g. if internet resources already exist), and cost of personnel time is likely the most significant.

Sample cost itemization tool

Below is an itemization of start-up and maintenance costs for integrating and administering PROs. Enter costs in the boxes below to determine:

Fixed Costs

Device or devices (e.g. iPads or other tablets). You may wish to purchase more than one device in order to administer PROs to more than one patient at a time:

Printer, if PRO results are printed out (printer is not a cost if integrated into EHRs or presented to provider on-screen at start of visit):

Recurring costs in 1 year

WiFi access (monthly fee X 12 months):

Paper, 1 page of PRO results per patient (no cost if electronic) multiplied by number of visits for which PROs are administered in a year:

Toner for printer. Number of cartridges needed depends on number of PROs administered. A standard cartridge prints 220 pages:

Salary associated with % full-time equivalent (FTE) for staff member setting up and overseeing use of tablets. In the PROgress study, staff estimated a maximum of 4 minutes per patient for explanation of procedure, setup, collection of device, and delivery of paper-based results. This estimate is based on the one-on-one interaction time of the staff member with the patient as well as time handing the tablet, and not the full completion time of the PRO assessment by the patient as the staff member often left the room and did other activities while the patient completed the assessment:

Total :

Sum

One of the biggest issues that lead to delays and practical barriers including unplanned costs with PRO implementation, involves integration with the EHR. Creating new platforms can be expensive and time consuming, integrating with EHRs is sometimes not feasible and the burden of the slow and/or complex EHR control processes have been noted as a hurdle.3 This is even before taking into account the frequent changes in EHR products that are occurring across many healthcare settings. Fortunately, stand-alone platforms can be used that are much less expensive than developing new platforms, that allow PRO collection to continue regardless of EHR changes and facilitate implementation with PRO feedback even before EHR integration.

PRACTICAL TIP

A plan regarding technical approaches (Chapter 3) is important when estimating costs. EHR-based approaches are not necessarily the most effective (due to many PLHIV not being linked to patient portals), efficient, modifiable, or practical. However, this is a quickly moving area and will need to be assessed on a site-by-site basis (Chapter 3).

1.3. Creating a business case for PRO implementation

Your organization may require a formal business case for PRO implementation in order to identify short- and long-term goals and associated budget requirements. This may include needs, solutions, approaches, risk assessments, and value analyses.

Table 3 shows an example of this format.

| Table 3. Example PRO business case format | |

|---|---|

| Potential Sections | Description |

| Executive Summary | Brief description of overall plan including goals, milestones, summary of implementation |

| The case for investing in PRO elicitation in routine HIV care |

|

| Statement of Goals and Objectives | Includes long and short-term goals |

| Service overview |

Describe proposed integration in more detail, including:

|

| Project team |

|

| Milestones and deliverables for implementation | Convey confidence in how the project will be managed and monitored |

| Financial Analysis | Carefully estimated cost of investment required; include start-up and recurring costs |

| Risk Management Plan | This section details risks specific to the business plan. This may include process failures such as IT/Wi-Fi, staff turnover etc. |

| Measurable and Achievable Outcomes | Based on the goals section of the business, determine how success will be measured |

2. ENGAGE STAKEHOLDERS

2.1 Identify stakeholders

Early stakeholder engagement facilitates successful PRO implementation and its sustained use. Stakeholders include clinic leadership, patients, providers, and staff, and may also include others, such as hospital administrators or researchers. Each brings a unique perspective, concerns, and valuable input.

The broad goal of improving care tends to engage stakeholder interest, with very specific concrete examples such as identifying otherwise undetectable suicidal ideation, depression, or inadequate adherence to ART, being very relatable goals that almost all stakeholders can appreciate. Furthermore, these types of goals have a strong evidence base supporting their likely success.

Individual stakeholder goals may vary. Early preliminary discussions to understand stakeholder concerns and goals can help tailor information and secure valuable support. For example, providers may be more motivated to adopt PROs to increase the appropriate diagnoses or identification of issues such as inadequate adherence, nurse managers may be concerned with impact on flow, patients may wish PROs included areas such as HIV stigma or social support to provide context to health needs, and administrators may want to know if PROs can help satisfy external reporting requirements such as the percentage of clinic patients who complete a mental health instrument. Regardless of the stakeholder or motivation, engagement early in the process can identify and address benefits and concerns around PRO implementation (see Address Common Concerns in this chapter).

2.2 Prepare demonstration of value

Stakeholder interest depends on clear demonstration of value relative to cost. Ideally, a value demonstration takes the form of a brief presentation or a simple summary sheet. A presentation demonstrating the impact of PROs on provider awareness and documentation of depression, substance use, and inadequate medication adherence is here.5 While clinical benefits such as increased provider awareness of risk behaviors are relevant for all HIV clinics, additional benefits may be applicable for specific settings (e.g. reporting requirements or meeting annual depression screening requirements for specific state-based payees). Providers have particularly valued improved identification of suicidal ideation and substance use.10,25

In the case of PRO adoption in the clinical setting, a value demonstration should consider who the beneficiaries are (e.g. the patient, the provider) and what the advantage unique to the stakeholder might be (e.g. better quality patient data for diagnosis, improved provider/patient interaction, more comprehensive care, and improved health outcomes for the patient).

PRACTICAL TIP

Provide a clear justification for PRO data collection, as providers and staff are more likely to support PRO implementation if they understand the value.3 Short practical examples are more compelling.

Example 1: Improve patient engagement in care via better detection of treatable problems. On average, ~30% of PLHIV in the US report depression at any one time, and this is associated with many poor outcomes such as mortality. 26 It is notable that even among PLHIV with known depression, there are substantial gaps in the depression treatment cascade with lack of follow-up to see if treatments are effective. 27 We plan to integrate a brief clinical assessment of PROs including depression to identify the ~20% of our clinic with undiagnosed or undertreated depression to improve care for those PLHIV.

Example 2: Reduce preventable death. Two patients in the past year were killed as a result of intimate partner violence (IPV). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has estimated that the rate of IPV among women with HIV is double the rate of those without HIV (~55%). 28 PROs may effectively detect IPV. We are also seeing increasing heroin overdoses. We would like to implement a brief clinical assessment of PROs to allow a standardized approach to screening for IPV, drug and alcohol use, depression, and inadequate adherence, to allow us to better identify those PLHIV in our clinic who may benefit from additional interventions such as addressing IPV and ensuring Narcan for those using illicit opioids.

2.3. Meet with stakeholders

Meeting with diverse stakeholders as a group presents an opportunity to describe the purpose of PROs, alleviate concerns or misapprehensions, and to coalesce support for their known value in improving care and clinical outcomes.5 An adaptable sample presentation for this purpose is here.

Beyond the presentation of static information, we recommend giving stakeholders the opportunity in this meeting to interact with PRO measures and their output in order to better understand the process and its potential. This step, in our experience, has been a key turning point in generating enthusiasm and helping stakeholders visualize integration into daily routine. An example of an electronically-administered touch-screen PRO assessment for this purpose is here, which your audience may self-administer on their own or other devices. Sample output, or the results generated for providers is here and in Figure 6 (Chapter 4). An interactive tool for determining average timing to completion for varied combinations of individual PRO measures is here. Screenshots of the interactive tool can also be found in Appendix 2.

Figure 2 shows a sample agenda for an initial meeting with stakeholders.

| Figure 2: Sample initial stakeholder meeting agenda |

|---|

| Initial orientation to PROs: |

|

| Further discussion could include: |

|

A sample presentation for this purpose is in Appendix 3.

PRACTICAL TIP

Bring tablets and a demonstration version. Showing how straightforward it is for PLHIV to complete and get started with an assessment is crucial to alleviate staff concerns. Shorten the agenda as needed to ensure adequate time for the demonstration.

2.4. Provide overview of value

A comprehensive overview of the potential value of PROs is available in the form of the PROgress Evidence Review and Summary, as a companion document to this Toolkit.

2.5. Address common concerns

Stakeholders will likely have many valid concerns about introducing PROs into their practice. Below is a list of common initial stakeholder concerns regarding the implementation and ongoing use of PROs. Many of these concerns have proven addressable in past integration efforts.

Table 4 summarizes common concerns, followed by suggestions regarding how they can be effectively addressed.

| Table 4: Common initial stakeholder concerns, and how to address them | |

|---|---|

| Common concern | How to address |

| PROs create too much additional work for providers in terms of the need to document additional non-urgent issues. | Evidence shows that while there is a modest increase in workload with respect to documentation, providers value the additional information that they believe may otherwise have been missed, such as suicidal ideation, depression, ART non-adherence, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behavior10,29

Additionally, there are ways in which PROs may reduce this burden. In the Review of Symptoms Index for example, patients select the degree to which they are bothered by symptoms; the most bothersome ones can be prioritized/prominently displayed in a results report (see example here Focusing on targeted domains (health topics) that measure key clinical domains that are highly actionable such as substance use can alleviate this concern |

| Addressing PRO results adds too much time to the visit | Evidence shows that providers perceived time expenditure as not having necessarily increased, but rather as having been prioritized differently29 |

| PROs take the focus of the visit away from the patient’s chief complaint and force providers to address issues that would not otherwise have been top-of-mind for the patient | It is true that the additional information potentially provided by PRO results likely impacts discussions. Additional issues may get raised that would not have otherwise been identified. PROs can focus on highly actionable and clinically-relevant domains that providers agree are important to address such as substance use. Alternatively, if a broader PRO assessment is addressed, providers can review results with patients and ask which concerns they are most interested in addressing today. The experience remains patient-driven, presuming the absence of more serious concerns found in the PROs (e.g. suicidal ideation) |

| PROs are redundant. I have great rapport with my patients and they are honest with me about their needs and behaviors already | Evidence shows that patients are more honest in responding to questions on a computer tablet than answering questions in person, particularly on sensitive topics.9,30-32 Social desirability bias among patients toward their providers may impede complete reporting even when there is good rapport. HIV care clinicians have expressed surprise at patients’ PRO responses, particularly on sensitive topics, among patients they assumed they knew well10 |

| Addressing an itemized list of symptoms and behaviors is at odds with my professional style, which prioritizes connecting with the patient as a human-being rather than a list of problems to be solved | PROs are not meant to replace communication with providers, but rather to enhance it. PROs have been shown to empower the patient to take inventory of their health and better prioritize their needs in preparation for their visit.23,33 PROs can be viewed as a means of amplifying, organizing, and articulating the patient’s voice in care. They allow relevant issues to be identified so the provider can focus the discussion in a productive manner in those areas most likely to benefit the patient rather than spending most of the interaction gathering information about potential issues |

| Patients will not tolerate a PRO assessment | Evidence does not support this. Across several clinical settings and diverse populations of PLHIV, tablet-based PRO assessments administered on site prior to the clinic visit have proven to be well-tolerated, with patients reporting high levels of satisfaction with the process23,24,33 |

| PROs will negatively impact clinic flow. | Prior implementations suggest minimal impact on flow after the initial ramp-up, if done well.6 The impact of PROs on flow is modifiable, and there are many ways to reduce it. Suggestions include minimizing the length of PRO assessment to include only the most clinically-important domains of care; varying the frequency with which specific measures are administered (e.g. annually for less mutable domains, such as gender identity); administering PROs only when patient has arrived sufficiently early or on time (or if the provider is running late); remote PRO completion |

| PROs require too much staff time to administer. | The staff burden required depends on the format of PROs used. This Toolkit is focused on tablet-based collection as it requires less time, patients prefer it and complete it more efficiently, there is no scoring or data entry steps, and results are available to providers in real-time. If using tablet-based data collection, the labor involved consists of explanation to patients of the procedure, peripheral monitoring to determine when the patient is finished, and device stewardship and sanitization. Depending on the clinic flow, these responsibilities can be performed by a dedicated staff member, or integrated into front desk staff duties (incorporated into check-in procedures), or integrated into MA duties (incorporated into rooming and completion of vital signs). By incorporating PROs into rooming or check-in procedures the amount of staff burden can be decreased but still exists |

2.6. Include providers in PRO selection process and output design

Without clear relevance or usefulness to providers, PROs will be less likely to succeed long-term in the clinic. Therefore, consider early engagement of providers to determine what PRO domains would be of most use to improve their ability to provide the best possible care for PLHIV, and by extension, patient outcomes.

Providers are the end-users of PRO data. The results need to be highly relevant, interpretable, and easy to interact with. To help ensure this, always include providers in decision-making processes on the content, format, and design of PRO results. This includes what form of presentation the reporting will take (e.g. paper vs electronic, multiple vs single time points), how scoring is displayed and explained (e.g. Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 items for depression [PHQ-9]), organization of information (e.g. which domains at the top of the page vs bottom), and aesthetics (e.g. use of color or bolding to highlight pertinent information). Early provider engagement helps ensure inclusion of clinically-relevant, actionable domains, and ultimately, investment in the PROs as a clinically-useful tool tailored toward your clinic’s specific needs. See the sections titled Select PROs: domains and attributes to consider, Format results and Create PRO assessment in Chapter 4.

PRACTICAL TIP

A very common concern among providers is that PROs will lengthen visits. 3 When presenting plans to implement PROs to stakeholders, emphasize evidence showing this is not likely the outcome. 29 Demonstrate the actual time to complete the assessment during stakeholder discussions using tablets and a demonstration assessment. Propose a plan for minimizing impact on flow, such as having

PRACTICAL TIP

Impact of PROs on clinical flow is an almost universal stakeholder concern. 3 Reassuring stakeholders with a clear plan to start slowly in order to minimize impact on care processes is crucial. PROs can then be expanded once any implementation issues have been addressed. Examples of successful roll-out approaches that have been used to minimize impact on flow include starting on the least-busy clinic days of the week, starting with one full-time provider invested in the success of PROs and able to work with the team during integration, and starting with a very targeted brief PRO assessment.

2.7. Secure implementation champion

One effective strategy for building momentum around PRO implementation is to identify or cultivate a ‘champion’ in the setting where PRO implementation will take place. This person is tasked with advocating for the use of PROs, inspiring the range of stakeholders and increasing/maintaining commitment to maintain momentum of PRO adoption. The champion will remain close to the process as it evolves and will serve as a communication conduit for all parties, including eliciting arising concerns and issues, and communicating plans and successes in navigating these as the project evolves. This person is often the clinic director – with a PRO coordinator acting in this role once implementation occurs. Champions provide leadership, guidance, and encouragement to stakeholders, and focus on the sustainability of the PRO implementation.

3. TECHNICAL CHOICES AND INFRASTRUCTURE

3.1. Understanding PRO Choices

A successful PRO implementation should integrate both treatment- and patient-centered perspectives into one health information system, which should be crafted to optimize the patient experience, to enhance the provider’s clinical use of the data, to minimize any challenges to clinic flow and efficiency, and to maximize population health utility of the information. In this context, population health may include clinic-level, research, and public health uses of the data.

The first major step is confirming that all stakeholders share the intent to implement computerized collection of PRO data. While PROs may be collected by paper, the manual approach, this will likely be dismissed once a variety of factors are considered. The disadvantages of paper-based collection include increased clinic workload to administer PROs and enter responses, decreased accuracy from required data entry, provider effort in summarizing data to realize clinical utility, and patient perceptions of both the utility and process of providing PRO responses. See Chapter 4 for more details regarding relative advantages and disadvantages.

The second step is deciding which of four types of PRO systems to consider:

- a commercial “standalone” PRO system that can be integrated with an EHR

- an EHR vendor’s “built-in” questionnaire tools

- a developed PRO system developed “in-house”

- a PRO system supplied as part of participation in a research or clinical network.

All EHR and standalone PRO system vendors highlight their system’s ability to gather PRO questionnaire responses, provide those responses to providers, and ensure they become part of the medical record. However, it is important to examine each of these four options carefully to compare: the true cost of acquiring, integrating and supporting any particular product; the experience of the patient in accessing the system and recording their responses; the experience of the provider in accessing and using a clinically-relevant summary of longitudinal patient data; and the ‘cost’ (licensing, implementation, maintenance) of persisting the data in the EHR – and if the data are persisted, whether that is done as a scanned image, an electronically-transmitted summary form and/or discrete observations. How the data are stored impacts the ability to derive secondary value, beyond clinical utility, from population health applications.

Often IT organizations strongly favor using tools from their existing EHR vendor, in order to avoid a new vendor relationship and contract, simplify implementation of interfaces, avoid a new set of security considerations, to advance an agenda such as increasing patient use of a patient portal system, or simply to make use of existing vendor support mechanisms. However, the impact of a choice made only on these technical and operational considerations can significantly impact the experience of the patient and the value to the provider, which should be paramount to maximize data collection and use.

Once the four types of PRO systems have been considered and an evaluation is determined, the approach that best balances function and cost, has provider support, and is acceptable to any applicable IT governance process, then the particular pathway choice will drive other technical needs (i.e. for software/operating system support, hardware platform, data storage attributes to support high data integrity, data center needs to ensure secure operation).

3.2. Identify Issues to Guide Choices

It may be helpful to organize the issues to be addressed according to the phases of gathering, using, storing, and reusing PRO data. These include:

- The flow of information from the patient to the provider

- The use of the information by the provider

- Storing the information to meet medico-legal requirements for medical record collection, retention, and accounting of disclosures

- Reuse of the data for population health purposes.

Gathering information from the patient:

- In what settings will the patient use the system? Only in the clinic? At home, or in another location of their choosing?

- What kind of support can be provided for in-clinic use?

- In what locations can the patient use the system prior to their clinic visits?

- What support is available for out-of-clinic use?

- Can in-clinic use serve as a “backup” plan for patient’s unable to complete PROs outside the clinic, and if so, how does the communication occur to ensure that the patient can be prompted? - Can the system deliver reminders to the patient to complete PROs, or to the staff that a PRO has not been completed prior to a visit?

- What hardware will deliver those reminders and what constraints does that place? - What devices will the patient use in clinic? Tablets or iPads are a common choice.

- Can concerns about damage or loss of in-clinic devices be assuaged?

- Are there valid concerns about device cleanliness?

- How will defective or mis-configured devices be identified and repaired?

- What level of duplicate devices are needed to ensure tolerance of faulty hardware? - Can the patient use the device of their own choosing out of the clinic? Can they use that device in clinic?

- Can they use their phone?

- Can they use a computer?

- What security considerations are there if they are using a device that is not theirs? - How do we validate the identity of the patient when initially enrolling them?

- How do we authenticate patients when they are using the system?

- Is that done in person, for in-clinic use?

- Do we sign them in with a patient-specific username/password and what kind of registration process do we use to support that?

- How do we manage support for recovering passwords, or other login issues?

- Does logging in present too much of a barrier to use and are there strategies such as one-time questionnaire links which can be used?

o What are the institutional concerns around using one-time links?

o How does it impact the data that can be shown to the patient?

o How does it impact the value to the patient? - What controls the patient’s periodic usage of the system?

- Can the patient use the system electively, like a diary in their control, or only on a fixed schedule, as if it were an in-clinic questionnaire?

- Can they edit/correct/revise their responses? How do they address errors?

- Can the system deliver reminders to the patient to complete PROs, or to the staff that a PRO has not been completed prior to a visit?

- What hardware will deliver those reminders and what constraints does that place? - Do we need to implement a patient’s “right be forgotten” in a particular setting?

- Does that conflict with the need to maintain records, or to make data available for population health uses?

Presenting information to the provider:

- How can the information be presented to the provider?

- Discrete values sent to an EHR and viewed through charting or table functions?

- Customized, domain-specific longitudinal patient summary? - How can the provider access those views of information?

- While logged into the EHR, using EHR tools?

- While logged into the EHR, viewing a static summary?

- While logged into the EHR, using an application within the EHR to view the data interactively?

- Similarly, the last two options may be options in a vendor system, locally developed system, or system provided as part of a research or clinical care network.

- Are there visualization considerations that create opportunities to overlook or erroneously interpret information?

- Especially if patients can use the system electively, are there visualizations which efficiently present a large amount of information? - Is viewing information closely linked to the providers documentation process?

- Are there “macros” or summary information that can be imported into the documentation?

Storing information into the medical record:

- Are the PRO data preserved as discrete observations in the EHR?

- Are they preserved in their entirety, or only in the form of scores or alerts?

- Are they preserved as a visit-specific longitudinal summary, imported or preserved in the EHR system and linked to a specific encounter?

- If not part of the EHR, are the data preserved in a system that meets reliability, security, assurance, and retention requirements under appropriate regulations?

- Are there other more general regulatory or policy considerations, such as privacy practices or security regulations or Institutional Review Board (IRB) guidance, with which the system has to comply?

Reuse of information for population health:

- Are there individual level metrics of frequency and completeness of use? Is individual level data collected from patients and providers to monitor satisfaction and barriers to use?

- Are there clinic level indicators of use available to show broad patterns of use and monitored for changes that might represent systematic barriers or enablers to use?

- Are there clinical level metrics based on aggregate outcomes of clinical significance, so that PRO data may be used to monitor patient-reported impacts of changes in care patterns?

- Are adequate data being collected to satisfy any research or public health goals for secondary use of those data?

- Are the PRO data represented using standard formats and value sets, such that extracted data may have its structure and meaning consistent with that form other systems?

As an example, in the PROgress study, after discussion with teams at St. Michaels Hospital and Midway Specialty clinics, including discussions with the IT staff, we addressed these issues as follows:

Gathering information from the patient: Initial implementations at both sites were based on in-clinic administration of the PROs on a tablet. This simplifies both the direct support for the patient in using the system, if needed, as well as the issues of identity verification and account management for the patients. However, this comes at a cost of flexibility of administration. Both sites were pleased with their choices, but both had trouble making the transition to remote use with the onset of COVID-19 concerns and the shift to telehealth visits.

Presenting information to the provider: Both sites valued integration with the EHR, however both were in transition to, or strongly considering new EHR vendors and would have needed a clear and economical path to integration with their existing vendors. We did explore both Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources (FHIR) interfaces and Substitutable Medical Applications, Reusable Technologies (SMART) on FHIR integration with one of the vendors, but exchanging enough information to secure a firm bid proved elusive and both sites elected to use automated printing of a results summary on PRO completion, and delivery of that summary to the provider at the time of the visit.

Storing information into the medical record: Both sites elected to scan the summary sheet into the electronic medical record since an electronic interface was not implemented and they were soon going to transition to other EHRs.

Reuse of information for population health: Both sites elected to rely on the built-in dashboard features in the administrative view to track usage and completion, and on the analysis data set download feature for further examination of population level responses. Midway requested a ‘whiteboard’ view to track waiting room completion status in real time in the provider room, which was implemented. This is similar to a feature that had been previously developed for another clinical setting and allowed a screen to always show progress of patients on the PROs in the clinic in real time.

3.3 Consider System Features

Table 5 describes considerations for the PRO system features, adapted from Fenton et al,34 which reflect a similar set of concerns.

| Table 5. Key considerations for defining PRO system characteristics data | |

|---|---|

| Key Consideration | Definition |

| EHR infrastructure | Existence and type of EHR system. Important to consider because of both degrees of data integration and feature comparisons, between EHR vendor PRO tools, PRO tools that can be integrated with the existing EHR, and standalone PRO tools |

| Data standards | Methods, protocols, terminologies, and specifications for the collection, exchange, storage, and retrieval of information associated with PROs |

| Dashboard design and alerting | Frequency and scheduling of alerts, the data displayed in the dashboard to monitor system performance and usage, the number of clicks or steps required to access information, whether there should be capabilities to temporarily mute or turn off certain features, and the types of icons and graphics that are recognized most easily |

| Data accessibility | The data gathered by the PRO system must be accessible at both the individual and population levels, with quality, timeliness, and accuracy appropriate for each intended use |

| Interoperability | The ability of different vendor systems and software applications to communicate, exchange data, and use the information that has been exchanged; interoperability is enabled by common data standards |

| Adaptability of technology | Changes in the usage of PROs across different patient groups and/or different health domains; this capacity to adapt to new health system needs requires processes to be defined and documentation to be in place for local developers |

| Adaptability of content | Consulting patients and providers, and using their input to determine how to collate data received; responds to the need to align PROs with patient/provider needs, or to translate the content into new languages |

| Translatability | The capacity of PROs to function across different types of mobile devices and operating systems; ensuring hardware and system compatibility with technologies that are adaptable to a variety of needs will greatly facilitate the scaling up and sustainability of PRO systems in new settings |

| Language | PROs must be delivered in a language or set of languages that is accessible by patients or family members reporting their outcomes, and the results must be delivered in a language that is accessible by providers or others who must understand and act on those results |

| Workflows | PRO usage must fit with the workflows and activities that both patients and providers undertake. Those workflows may be a change from existing workflows but planning for that change facilitates effective implementation. |

| Storage needs | PRO data used for clinical decision making must be considered part of the medical record and, whether stored within the EHR or apart from it, is subject to regulations and policies pertaining to data reliability, integrity and retention |

| Data security and privacy | PRO systems and the storage of data from PROs must comply with applicable privacy and security regulations | Adapted from Fenton et al.34 |

3.4. Consider Data Quality

System features may include creating a dashboard to enhance usage monitoring, improve data accessibility, and monitor data quality. Minimizing data errors within the PRO system is critically important. Errors or missing data can be reduced through automated data quality assurance measures that assess data for inconsistencies (e.g. validation rules built into the application), and through consideration of issues that discourage patients from starting or completing PRO sessions.

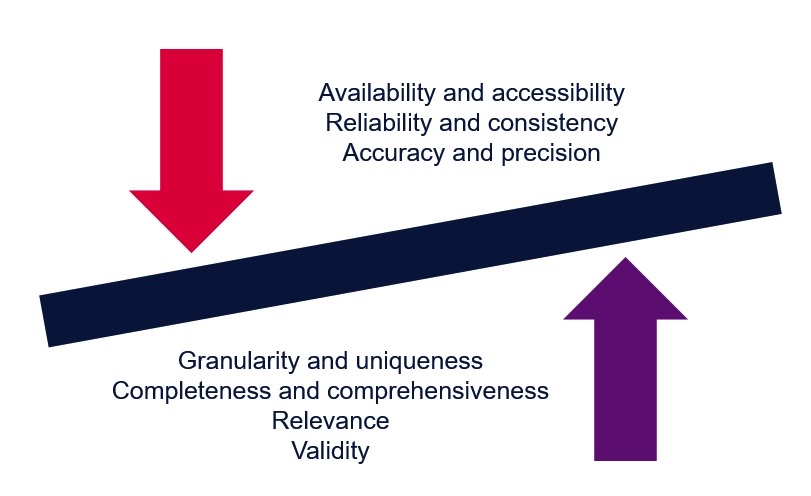

Figure 3 describes the characteristics that define data quality.

Figure 3. The characteristics that define data quality

Adapted from Fenton et al.35

Accuracy and precision refer to the exactness of the data. Accuracy in healthcare is worth high levels of investment. The data must not contain errors and must convey the correct information without being misleading. PRO answers that are considered valid or legitimate based on the survey’s requirement are allowable.

At the same time, it is important to realize that requiring a patient to answer a question does not guarantee accurate data, any more than requiring a healthcare provider to acknowledge an alert guarantees their thoughtful consideration of the underlying information. Patients should be given a pathway through the PRO process which encourages them to provide information useful to their care, and to understand the benefit of providing that information.

There must be a valid reason to collect the data to justify the time and effort required. PRO data collected that is not relevant can misrepresent a patient’s health status and drive inaccurate clinical decision-making. Incomplete data collection can lead to incomplete understanding of patient health. Providers need the right level of access to the PRO data to adequately evaluate the data in a timely manner.

There must be a reliable mechanism that collects and stores the PRO data without inconsistency or variance. The level of data detail is important, since inaccurate decisions can occur if the data is not clearly presented. Simple raw data may have a different meaning than data that has been aggregated and summarized.

A PRO system that offers a wide range of software features can adapt to specific patient or provider needs without significant additional programming and supports reporting and data visualization solutions.

3.5. Resources

Guidance on Infrastructure

- Snyder C and Wu AW, eds. Users’ guide to integrating patient-reported outcomes in electronic health records. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University. 2017. Funded by Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI); JHU Contract No. 10.01.14 TO2 08.01.15. Available here. Accessed October 2020.

- Coons SJ, Eremenco S, Lundy JJ, et al. Capturing patient-reported outcome (PRO) data electronically: the past, present, and promise of ePRO measurement in clinical trials. The Patient 2015;8:301-9.

Other Helpful Information or Examples

- ePROs in clinical care: guidelines and tools for health systems. 2020. Available from: https://epros.becertain.org. Accessed October 2020.

- Clinical data capture and management evaluation checklist. Available from: Oracle Data Sheet.

- Review of data accessibility methods in healthcare. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/280722426_REVIEW_OF_DATA_ACCESSIBILITY_METHODS_IN_HEALTHCARE. Accessed October 2020.

- The MAPS Toolkit: mHealth Assessment and Planning for Scale. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2015. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/185238. Accessed October 2020.

- REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) is a secure web application for building and managing online surveys and databases. Available from: http://projectredcap.org. Accessed October 2020.

4. CREATE PRO ASSESSMENT

There are several decisions to consider while creating the PRO assessment. These include determining the mode and frequency of administration, which PRO measures to include and in what order, what skip patterns are needed within the assessment, and how the results will look. This section helps fully consider each of these decisions.

“What do we want to know about our patients that would allow us to do a better job — to increase our knowledge and take action?”

- Clinic Director, speaking about their implementation experience and PRO selection.

4.1. Decide mode of administration

PRO measures may be administered in electronic or paper format. We briefly describe the advantages of each below.

Advantages of paper administration:

- May be more familiar to patients with low computer literacy

- Quick, lower-cost start-up.

Advantages of tablet-based administration:

- Ability to automate skip patterns within assessment so that patients only receive relevant questions (e.g. no smoking frequency questions shown if indicates not currently smoking), reducing time burden. The ability to integrate skip patterns dramatically reduced patient burden and therefore impact on clinic flow. It may be one of the most important advantages of tablet-based collection

- Patients prefer or perceive advantages to tablet-based over paper-based administration21,22,36

- Automated scoring within domains (e.g. PHQ-9). This reduces errors and also staff burden as no scoring by staff is required. It facilitates having scored results available to provider in real-time to enable clinical care impact

- Ability to link PRO responses to real-time pager alerts to clinic staff for high-risk patients, such as when suicidal ideation is endorsed. Among clinics that are also doing research, can use same approach to automate pages for other reasons including study recruitment

- Ability to administer in multiple languages yet easily interpret results

- Generation of real-time, comprehensive summary of results, with potential to illustrate differences between time points using graphics

- No physical space required for paper feedback form data storage. Furthermore, depending on goals, additional benefits can include:

- Potential for remote administration such as for telehealth visits with real-time results delivered to clinic staff

- Programming flexibility allows for patient-specific administration, such as showing specific PROs to select patients at select time intervals based on historic responses or risk factors

- Ability to synchronize with audio accompaniment when needed for PLWH with lower literacy levels or those with poor vision

- Easier to compile population-level data for analysis

- Potential for information to populate EHR as discrete data.

While paper-based administration may be easy to implement quickly at a low start-up cost, we strongly recommend tablet-based administration given advantages in reducing patient burden through algorithmic and skip-patterned administration, automated real-time alerts and scoring interpretation, and staff data entry burden, as well as patient preference. Given the burden on staff of scoring instruments when using paper-based collection, using a computerized approach has also been found to be less expensive in the long run for doing anything but the smallest number of assessments36,37 and tablet prices have recently been continuing to decrease.

In Figure 4, we offer considerations when selecting and programming a tablet-based mode of administration.

| Figure 4. Considerations for tablet-based PRO administration |

|---|

| Location: |

|

| Media (tablet, desktop, laptop, phone): |

|

| Language: |

|

| Patient experience: |

|

PRACTICAL TIP

Adding audio options to tablet-based PRO collection may be useful if working with a very low literacy population or those with vision problems, but for many patients it will increase completion times substantially and therefore should be avoided in order to minimize patient frustration and impact on flow.

4.2. Select PROs: attributes to consider

A key consideration when implementing PROs is how the information will support clinical decision-making and improve an individual patient’s care.

- What would be helpful to know about patients that cannot be easily or necessarily revealed through lab results or direct observation during the visit?

- What lines of inquiry might patients more comfortably and comprehensively answer in a computerized assessment, relative to face-to-face discussion?

- Most importantly, what PRO domains or health topics are directly actionable and eliciting and acting on the information would result in an improvement in care?

There are many domains of inquiry critical to HIV management and amenable to PRO assessments. Examples include depression/suicidal ideation, ARV medication adherence, alcohol/substance use, and HIV/sexual transmitted infection transmission risk behaviors. In addition, PROs offer an opportunity to explore social and context-based domains, such as partner violence, housing, social support, HIV stigma, and health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Figure 5 shows key factors needed for selecting PRO domains.

| Figure 5. Key factors in selecting domains to include in a PRO assessment |

|---|

Once the desired PRO domains are identified, consider which PRO measure is most appropriate within each domain. To ensure consistent uptake and relevance, a PRO measure used in clinical care should ideally be:

- Brief – the smallest number of items possible to provide the desired insight

- Validated – accurately measures what it says it will

- Easy for patients to understand (comprehensible to 6th grade literacy level)

- Easy to recall (e.g. shorter vs longer recall periods, particularly for mundane behaviors)

- Interpretable by providers at a glance.

Note that while many PROs are free of charge in the public domain, others require licenses and sometimes require fees or developer notification before use. In addition, requirements for use may change over time. Many high-quality instruments are available that do not require a license for use and in most circumstances may be preferable.

Table 6 lists a number of PRO domains relevant to HIV care.

| Table 6. Examples of PRO domains and measures relevant to HIV care | |

|---|---|

| Patient-reported… | Example of commonly used measures |

| Symptoms | |

| Depression | PHQ-938,39 |

| Anxiety | PHQ-5,38,39 GAD-740 |

| HIV-related symptoms (past 4 weeks) | HIV Symptom Index41 |

| Behaviors | |

| ART adherence (multiple recall periods) |

Self-Rating Scale, 30-day visual analog scale, AACTG adherence instruments (7-day missed dose, last missed dose, weekend missed dose)42-44 |

Nicotine use (lifetime, current)

|

Bruneck study measure,45 e-cigarette measure adapted from Bruneck (not published, available from CNICS) |

Drug use (specific drug list should be modified to address those drugs used in individual clinics)

|

Modified ASSIST for drug use46,47

|

| Alcohol use | AUDIT/AUDIT-C for alcohol use48,49 (AUDIT-C alone, or AUDIT-C with full AUDIT for those with hazardous alcohol use scores on the AUDIT-C) |

| STI risk (past 3 months) | Sexual Risk Behavior Inventory50

|

| Physical activity (past month) | Lipid Research Clinics Questionnaire41 |

| Substance use treatment history | |

| Substance use treatment (past year for all substances, ever for alcohol) | Treatment Services Review (adapted)51 |

| Identity | |

| Sexual orientation (current) | Not published, available from CNICS |

| Gender identity (current) | Not published, available from CNICS |

| Basic Needs | |

| Housing type and stability (past month) | CNICS Housing Measure52 |

| Exposure to violence | |

| Intimate partner violence (past year) | Intimate Partner Violence 4-item measure (IPV-4)53

|

| Childhood household violence (before age 18) | Adverse Childhood Experiences-International Questionnaire (ACE-IQ) (adapted)54 |

| Social dimension | |

| Social support (current) | Multifactorial Assessment of Perceived Social Support-Short Form (MAPSS-SF)55 |

| HIV-related stigma (current) | HIV Stigma Mechanism Measure (adapted)56 |

| QoL | |

| HRQoL (current) | EQ-5D57 |

| HIV/AIDS Targeted QoL | HAT-QoL items: perception of medication burden |

PRACTICAL TIP

Keeping assessment length short (<10 minutes) facilitates integration, minimizes patient burden, and decreases impact on clinic flow.

I think at first just start small. One of the things that we had to do too is prioritize our surveys… because you don’t want patients to sit there and complete 20 minutes’ worth of survey, (if) the providers are ready to see them. So, you have to be conscious of how much you’re asking the patient to do and what the impact will be like on their workflow.

- Implementer from a large US HIV clinic

4.3. Identify scoring and interpretation needs

In order for providers to easily review and process PRO results, choose measures with clear scoring and missing data guidelines. PRO results may have a range of different outputs of value. For example:

- Total scores based upon all questions

- Scores that are based on a discrete concept or sections within a PRO

- Scores based upon a single-item.

Some PROs require an algorithm that helps convert responses into scores that are easy to interpret and explain, such as a single number; some PROs simply require answer scores totaling up.

The scores can then be compared against an interpretation grid. For example, a depression score of 24 from a depression severity questionnaire may suggest ‘severe depression’; it is important to understand the sensitivity and specificity of the cut-offs.

It may also be valuable where a PRO measure provides:

- Reference scores for ‘similar’ patient groups that allow providers to compare their patients with similar patients e.g. those on the same type of medication

- Reference scores for PLHIV, which then allow the provider to compare individual patient scores with the average of a larger population

- Reference scores for general population, which allows the provider to compare an individual patient score with a normative score

- Linking scores to clinical practice guidelines.

The value in an approach that enables a comparison of the change in a patient’s score over time should also be considered.

An example of interpretation guidance is presented in Table 7 for the PHQ-9.39 The PHQ-9 captures the frequency of depressive symptoms experienced in the past 2 weeks by asking 9 questions. The response options to each question are ‘not at all (0)’, ‘several days (1)’, ‘more than half the days (2)’, and ‘nearly every day (3)’. The PHQ-9 has been used to make a tentative diagnosis of depression in at-risk populations, and it has been validated for use in primary care.58 To score the PHQ-9, the totals for each question are summed to reach a total score (maximum 27).

| Table 7. Examples of PHQ-9 scoring | ||

|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | Provisional diagnosis | Treatment recommendations |

| 5-9 | Minimal symptoms | Support, educate to call if worse |

| 10-14 | Depression Dysthymia Major depression, mild | Support, watchful waiting Antidepressant or psychotherapy |

| 15-19 | Depression, moderately severe | Antidepressant or psychotherapy |

| ≥20 | Major depression, severe | Antidepressant or psychotherapy (especially if not improved on monotherapy) |

4.4. Determine order of PRO measures in assessment

The chronological order in which PRO measures are placed in the assessment may have an impact on your patients’ response. We recommend beginning the assessment with a relatively benign domain, before building up to more sensitive topics such as sexual risk behavior, intimate partner violence, or substance use. Another consideration is that you may want to place the measures with the highest clinical relevance (e.g. suicidal ideation, ART adherence) earlier in the assessment in order to ensure that the patient completes the most critical information.

4.5. Determine frequency of administration overall and for each measure

After selecting domains and measures of interest, consider ways to minimize the patient time burden for completing PROs. This includes length of time for completion of assessment, the frequency with which patients will be offered PROs, and the frequency with which patients will be shown specific measures.

A tool for estimating the average length of time your PRO assessment will take to complete can be foundhere.

To establish the desired frequency with which patients will be offered the PRO assessment, consider the intervals in which your clinic’s patients typically are seen for routine visits. You may wish to administer PROs no more frequently than every 3 months, every 6 months, or annually, depending on timing of visits and your patient population’s needs. More frequent assessment may yield richer information, however, administering PROs too frequently may frustrate patients and increase staff burden and clinic flow impact.

PRACTICAL TIP

Occasionally PLHIV come to clinic very frequently (e.g. for wound care, intravenous antibiotics, other reasons). It is therefore important to set a PRO eligibility window so that PLHIV who are in clinic multiple times in the same week are not asked to complete them repeatedly. It will both annoy PLHIV and impact clinical burden.

An electronic PRO platform can be programmed to show individual PRO measures at specific time intervals. Not all PROs may need to be administered at every visit. For example, gender identity and sexual orientation are less prone to change relative to other domains, and so might be asked only every 2 years or even less often. Other domains, such as family history of chronic conditions, only need to be asked once.

An electronic PRO platform can also be tailored to administer individual measures with varying frequencies, based on an individual patient’s previous responses. For example, for an older patient who previously indicated having never smoked in the PROs, it may not make sense to ask about smoking habits on each subsequent visit; this question could be skipped in lieu of domains more relevant to that patient, and revisited less frequently (e.g. every 2 years). Conversely, patients who in previous PROs endorsed specific symptoms or risk behaviors, might be shown corresponding PRO measures more frequently. For example, a patient that indicated intimate partner violence six months ago likely needs more frequent assessment than a patient that has consistently indicated not experiencing it.

4.6. Format results

Output generated from PROs must be easy to interpret at-a-glance in a busy clinic setting. Ideally the results should also be formatted in a way that supports sharing or communication to the patient.

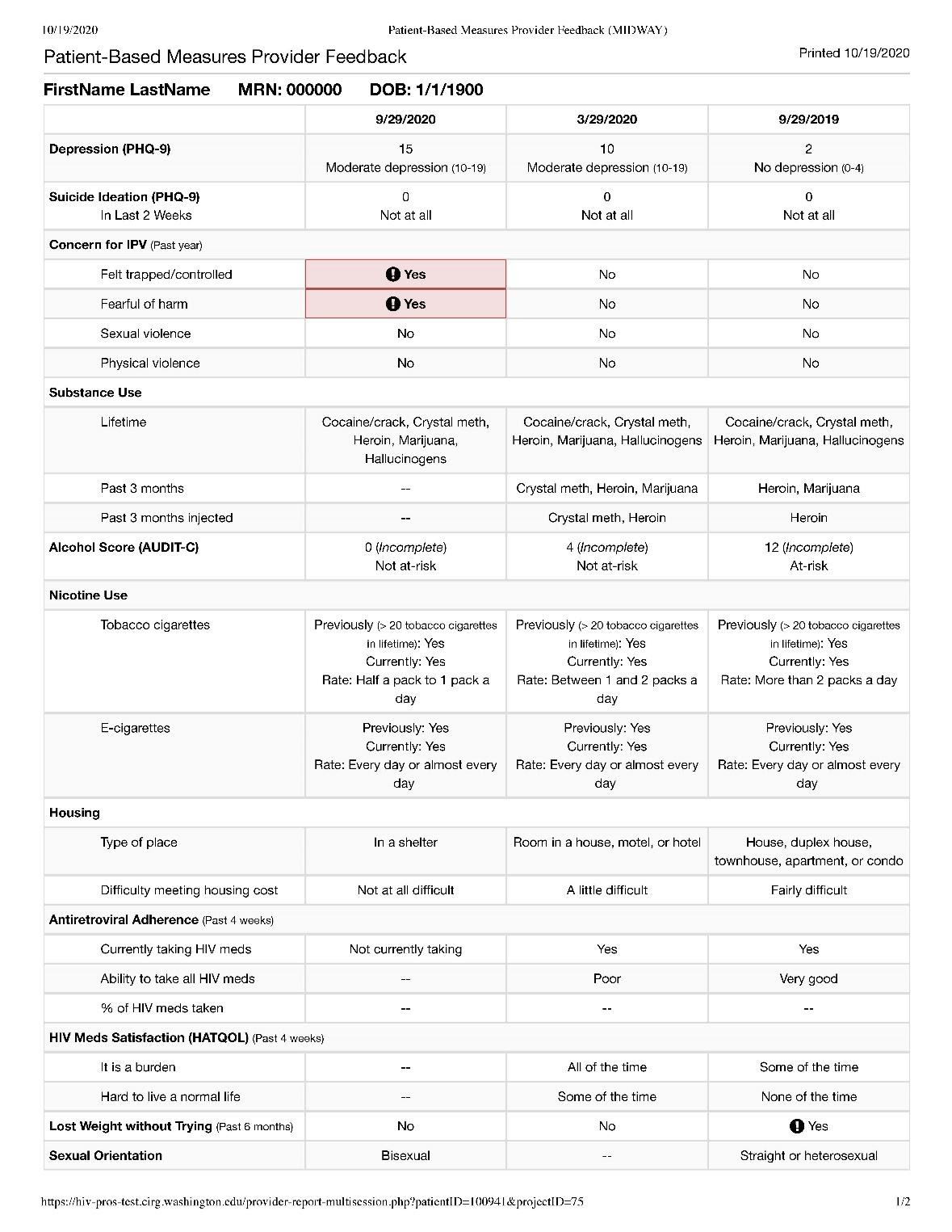

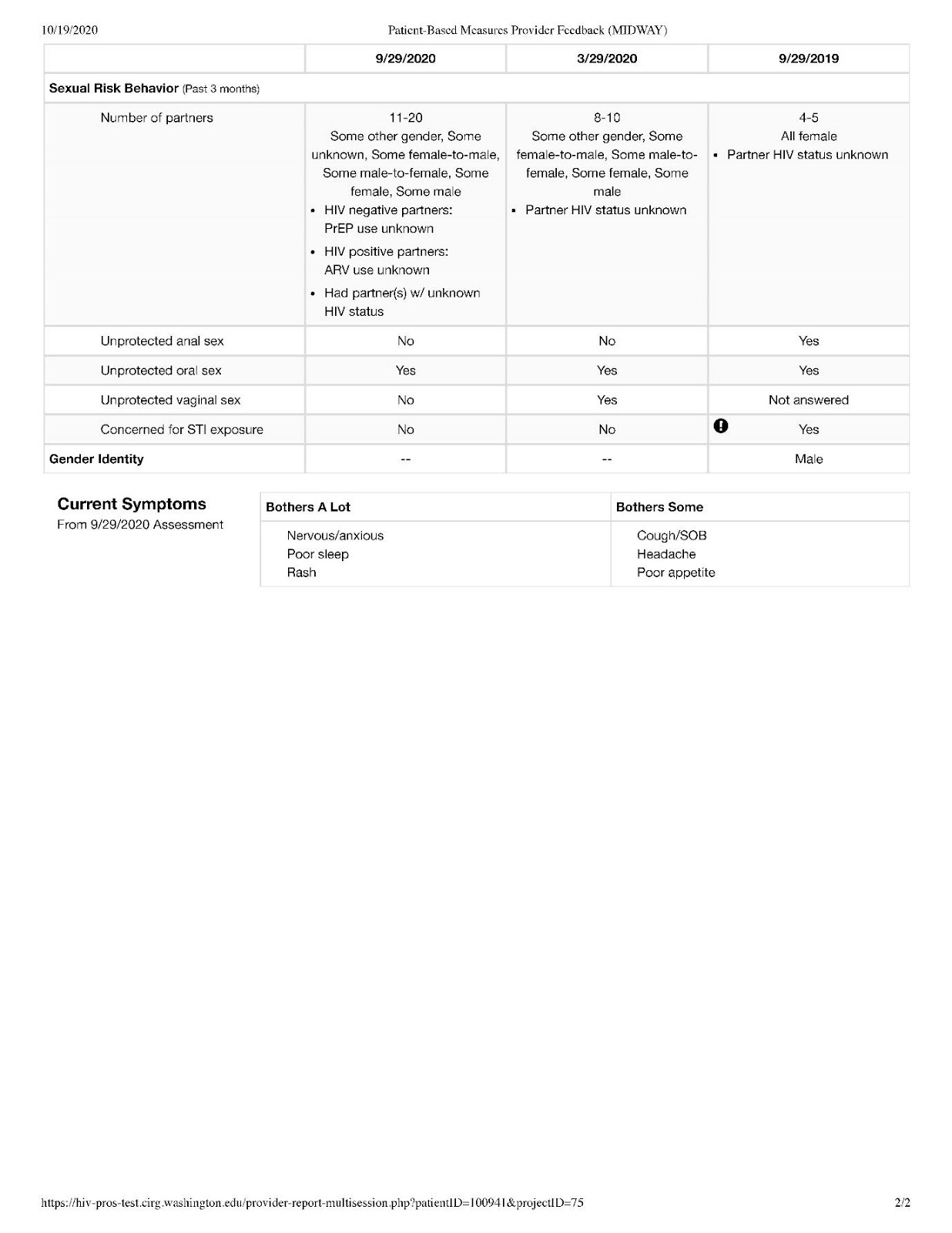

Figure 6 shows a sample PRO summary report (based on a fictional patient) illustrating a means for displaying PRO results across multiple time points. In this example, time points are retrospective moving from left to right, with alerts indicated by bold exclamation points to get the provider’s attention. The use of color and shading may also promote readability.

Figure 6. Example patient-reported outcomes provider feedback

4.7. Build your own PRO assessment

After considering the PROs you would ideally like to administer to your patient population, as well as the frequency with which you would ideally administer individual measures, we recommend calculating the potential time burden in advance of implementation. Below is an interactive tool to help calculate the anticipated average time burden to completion for several commonly used PRO measures. Multiple selections calculate a total anticipated average time. This tool may help demonstrate to stakeholders the number and nature of PROs that could be potentially queried, and the anticipated time burden and impact on clinic flow.

try it yourself here

4.8. Resources

- International Society for Quality of Life Research (prepared by Chan E, Edwards T, Haywood K, Mikles S, Newton L). Companion Guide to Implementing Patient Reported Outcomes Assessment in Clinical Practice, Version: February 2018. Available from: https://www.isoqol.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/ISOQOL-Companion-Guide-FINAL.pdf. Accessed October 2020.

5. OUTLINE WORKFLOW

Once you have decided on the mode of administration, which domains of care to measure, which measures to use, the average length of the assessment, and the format of PRO reporting, you are ready to begin visualizing the specifics of integrating PROs into your clinic’s workflow.

5.1. Select workflow: when, where, and how to administer PROs

There are three key ways to integrate PROs into your clinic’s workflow. Each has advantages and disadvantages, described below.

Remotely, prior to appointment.

In this option, PLHIV are asked to complete a PRO assessment in their own time and on their own devices before the appointment begins. Results are either uploaded to an EHR or printed out before the appointment by clinic staff and delivered to the provider and relevant staff.

ADVANTAGES:

- Minimal impact on clinic flow

- Patient controls timing and location of response.

DISADVANTAGES:

- Difficult to respond to emergencies in real time, such as suicidal ideation or intimate partner violence (e.g., if endorsed after business hours)

- Excludes patients that do not have access to electronic devices.

On-site at the beginning of an appointment.

In this option, PLHIV complete the PRO assessment upon check-in for a clinic appointment. For many clinics, PLHIV wait long enough on average to complete a brief assessment before their provider appointment. Other clinics with limited wait times may need to schedule the appointment time 15 minutes earlier to allow enough time to complete the assessment. Front desk staff, or a MA sets up the assessment on a touch-screen tablet. This is often done in conjunction with measuring vital signs.

ADVANTAGES:

- Up-to-the minute information on patient health status

- Ability to respond quickly to emergencies, on-site and in real-time

- Creates agenda for how time may be best spent during appointment

- Includes everyone regardless of whether they have devices.

DISADVANTAGES:

- PRO completion is dependent on patient punctuality or provider delay, in order to avoid disruption of clinic flow.

A combination of both approaches.

In this option, PLHIV are asked to complete a PRO assessment in their own time and on their own devices before the appointment. Some PLHIV do not have access or will not complete the PROs remotely. Those who do not complete the PROs remotely are then asked to do it when they come to clinic.

Advantages include all of the above advantages. In addition, by having some of the PROs completed in advance, it decreases clinic flow burden. Finally, it provides options in the current era where a larger proportion of clinic patients are being seen via telehealth in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.2. Define staff roles and centralize responsibility

Consider each staff member in the clinic and what role each of them play (e.g. provider, front desk, MA, other staff) in administering, tracking, and responding to PROs. A designated staff member is needed in order to ensure the steps of PRO administration are followed through for each patient. While we recommend that this responsibility falls upon a single individual that champions the collection of this data overall, other individuals, such as MAs, may be designated to act as ‘point people’ for PRO collection on a day-to-day basis.

You will want to designate in advance: